(1891–1980)

Childhood

Dorothy Pulis Lathrop was born on April 16, 1891 in Albany, New York to Cyrus Clark Lathrop, a businessman, and I. Pulis Lathrop, an artist. Lathrop recalls art being a part of her life from an early age. The creatively charged atmosphere in the Lathrop household must have been great because Lathrop’s sister Gertrude became a sculptress.

She also credits her paternal grandfather, who owned a bookstore in Bridgeport, Connecticut, for fostering her love of books. This early exposure to literature fired her desire to write and, later, to combine it with her love of art.

Education

Lathrop studied art for three years at the Teachers College of Columbia University and graduated with a teacher’s diploma, which pleased her father, a practical man who did not believe that any one could make a living at art. She also studied illustration at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts and the Art Students League in New York City.

Professional Career

Teaching art for two years at the Albany High School made her realize that she would prefer illustrating children’s books. Her first illustrated book, Japanese Prints by John Gould Fletcher, was published in 1919 but unfortunately the publisher went bankrupt before she received payment. Nonetheless, her career was off and running because a new book illustrated by Lathrop appeared almost every year.

For many years, the two sisters shared a studio with their mother, which they soon outgrew. The two sisters moved into a house and had a two-room studio built in the back. Gertrude was in the habit of bringing home little creatures to model for her sculptures. It wasn’t long before Lathrop found that she enjoyed drawing animals, and started to write her own stories which included animals.

In 1938, Lathrop was honored to be the very first recipient of the Caldecott Medal for her work on The Animals of the Bible, text by Helen Dean Fish. You can read her acceptance speech and the biographical paper written by her sister Gertrude at the Bud Plant web site. In the foreword ofThe Animals of the Bible the author states:

“During the drawing of these pictures, the artist studied not only the fauna but the flora of Bible lands and times, and each desert rose as well as each goat and turtle dove is as true to natural history as is possible to be.”Between book assignments, Lathrop enjoyed wood engraving. Like her books, she preferred animals for her subjects, becoming quite proficient at the process, winning several awards. Lathrop received a Library of Congress prize in 1946 where her work is represented in their permanent collection. Later in life, Lathrop moved to a small town in Connecticut where she enjoyed showing her pet dogs in dog shows. Lathrop died December 30, 1980 in Falls Village, Connecticut.

Influences, Style & Technique

I have not found any mention of any of Lathrop's early influences but Lynn Ellen Lacy, in her excellent book Art and Design in Children’s Picture Books, has this too say about Lathrop and her work:

“Lathrop’s stature as a color illustrator in the 1920s and 1930s was equal to that of her Art Nouveau contemporaries in fantasy, fellow Americans Jessie Willcox Smith and Maxfield Parrish, the popular Dane Kay Nielsen, and British subjects Edmund Dulac and Arthur Rackham.”She has worked in oil, watercolor, pen and ink and lithographic pencil. Much of her black and white work is high in contrast featuring large areas of black, yet her delicate pencil drawings in Bells and Grass can be so soft.

Raison d’Être

Certainly, the artistic household that Lathrop grew up in had much to do with fostering her creativity.

“My mother . . . is a painter. It undoubtedly was seeing her at work, being in her studio, and there encouraged to use her brushes and paints that gave me my interest in art. From her came much of my training in paint, and talk of art and artists was from a very early age part of my daily life.”But for Lathrop, there was another driving force, From her Caldecott Medal acceptance speech:

“… For a person who does not love what he is drawing, whatever it may be, children or animals, or anything else, will not draw them convincingly, and that, simply because he will not bother to look at them long enough really to see them. What we love, we gloat over and feast our eyes upon. And when we look again and again at any living creature, we cannot help but perceive its subtlety of line, its exquisite patterning and all its unbelievable intricacy and beauty. The artist who draws what he does not love, draws from a superficial concept. But the one who loves what he draws is very humbly trying to translate into an alien medium life itself, and it is his joy and his pain that he knows that life to be matchless.”

Children’s Books Written/Illustrated

|

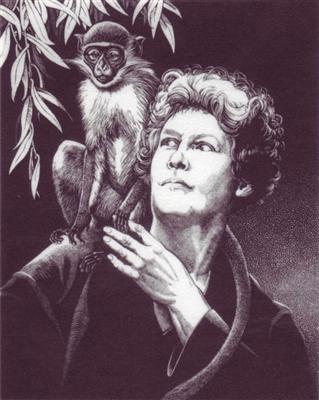

Dorothy Lathrop, 1949, self-portrait, engraving, "Jaspa and Me"

Dorothy Lathrop, 1923, Crossings by Walter de la Mare

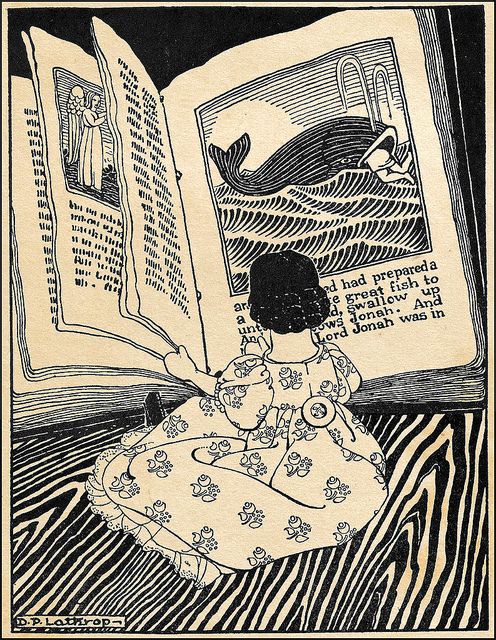

Dorothy Lathrop, 1934, illus. for her own The Lost Merry-go-round

Dorothy Lathrop, 1930, engraving, "Spring Song"

Dorothy Lathrop, 1927, illus. for The Princess and Curdie by MacDonald

Dorothy Lathrop, 1929, illus. for Hitty, Her First Hundred Years by Rachel Field

Dorothy Lathrop, 1942, Mr. Bumps and His Monkey by Walter de la Mare

BIOGRAPHICAL PAPER

by Gertrude K. Lathrop

Dorothy P. Lathrop

I REMEMBER that I was a chunky, matter-of-fact child of five or six when I used to follow Dorothy through the woods. I tried to move quietly for fear of frightening away the fairies. But somehow sticks snapped under my feet and branches swished as I crashed after her. Dorothy seemed to know just how to move to avoid the twigs that cracked and the branches that reached out to grab. This may have been why it was always she who saw the fairies. When we came upon a moss-lined hole at the base of a tree, we bent down, listened and breathed lightly - listened until the roaring of our ears would have drowned out any fairy words spoken deep in the earth. Being a practical child, I wondered why fairies would want to live in the dark, damp ground, no matter how beautiful their doorway.

There were other times when Dorothy built tiny houses in the woods in the hope that the fairies might adopt them. These were made of little twigs and roofed with moss. She found fat hummocks of green moss for seats and footstools. Other sticks quickly became fences, and the flower beds bloomed with bright, redtipped lichens. As we left the completed house and garden at dusk, she often laid a scarlet wintergreen berry inside, a special offering to the fairy queen.

The fairies must have come and been grateful, for I felt that they guided the shears of my half-grown sister as she skillfully cut their images from paper, and her paint brush, too, as she gave them long blond hair, delicate wings and many-colored dresses. And there was a golden crown for the fairy queen. I thought they were wonderful.

One of Dorothy's playmates, filled with longing to see beyond her own everyday world, wrote this wistful little note:

" Dear fairy that Dorothy Lathrop seen last night, I hope you will like our presents that we send up. My address is Miss Jessie Ryder. Please come and see me will you."

" Dear fairy that Dorothy Lathrop seen last night, I hope you will like our presents that we send up. My address is Miss Jessie Ryder. Please come and see me will you."

The plays that were given in my mother's studio were always fairy plays. My sister's greatest regret was that she could never be the princess or the fairy queen. She knew only too well that, because her hair was black, she must be the wicked witch.

Books have always been a large part of her life. Many miniature volumes filled the bookshelves of her doll house. Each little book was made of many tiny sheets of blank paper, but every one had a gaily colored cover bearing the name of some favorite story - The Light Princess, The Princess and Curdie, Mopsa the Fairy and Sara Crewe were among them. It is interesting that she chose some of these same books to illustrate when she grew up and made pictures for other children.

Our mother's studio is on the third floor of our house. Before civilization crowded in from every side, the windows overlooked field after field rolling back toward the distant Helderbergs and Catskills. Many mornings I would hear my mother stirring before dawn. The quiet early mornings belonged to her. No one was about to come between her and her beautiful out-of-doors as she sat with her sketch box on her lap. She loved to paint the trees and fields that were just visible through the morning mist. She worked swiftly to finish before the sun dispelled the mist and brought the hazy landscape into sharp detail. The purity and beauty of a heavy snow thrilled her as nothing else did, and she often said in a rapturous voice, " It's a fairyland! It's a fairyland!"

She loved all the beautiful little things in nature - the flowers, the mosses, the bright-colored toadstools - everything that grew. She often looked through her small magnifying glass at a miniature flower, its detail too minute for the unaided human eye to see, and marveled as the high-powered lens revealed a beauty and perfection as lovely as any orchid. It was our mother's enthusiasm and reverence for all things beautiful that gave us the eyes to see, and gave to my sister the wish to surround the fairies and animals in her books with an almost endless variety of plants and flowers, drawn with the greatest of care, it! the hope that she might catch even a little of nature's superlative beauty. Our mother encouraged us to draw all through our school days and, because of this encouragement and training, Dorothy won the medals and school honors in art all along the way.

Our father was a practical man who mistrusted art as a means of earning a living. It was he who insisted that any art training for my sister should lead to a teacher's diploma. Three years at Teachers College, Columbia, where she majored in art and also took all the English and writing courses offered, gave her such a diploma. The fourth year she chose to study illustration at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

She did teach art in the Albany High School for two years. And then one day at the lunch hour as she and a fellow teacher turned the pages of an illustrated book, she said that she wished that she could draw like that.

You wouldn't be here if. you could," said the other teacher crisply. And my sister thought with a little shock, " I may not be a Howard Pyle, but what am I doing here when I want to illustrate?"

Then began the trudging from publisher to publisher with an enormous portfolio that prompted the more chivalrous editors to carry it for her back to the elevators. Her first small set of drawings was done for a Boston publisher who went bankrupt before paying for them. After that, Alfred Knopf, then a very young publisher, offered her Walter de la Mare's The Three MullaMulgars to illustrate. Incredible good fortune for a novice illustrator! Magic and beauty to try to translate into line and color! W. H. Hudson's A Little Boy Lost followed, then other books from other publishers, all of which she found a joy to illustrate. But I think that she was never happier than when working with the poems and stories of Walter de la Mare.

It was Louise Seaman who encouraged her to make her own story-picture books. The first of these was The Fairy Circus, almost the last of her fairy work. After that her interest turned to animals, for which I perhaps am largely responsible. The animals I brought home for models for my own sculpture, quickly found their way into books - my two little lambs into Bouncing Betsy, my young kid into The Little White Goat, and my flying squirrels, that raised their families in our big outdoor cage, into Hide and Go Seek. This book, I think, is especially dear to her heart, possibly because we found the little creatures themselves such enchanting pets, or because of the pleasant trips we took each week to the woods to see how much farther the fern fronds had uncurled and what new flowers were in bloom, so that spring in this book keeps proper pace with the growth of the baby squirrels. Each plant is drawn with the same loving care she lavished on the squirrel portraits and shows the joy she took in leaf and animal alike.

But not all of the models were of my choosing. Lupe, the red squirrel from South America, was rescued from a pet shop by my sister. The Pekingese puppies in Puppies for Keeps and Puffy and the Seven Leaf Clover were bred, and later some of them shown to their championships, by her. They posed squirming on her lap and chewing the edges of her drawing board. Since she could not bear to toss it out into the snow, the mouse family in The Littlest Mouse, lived in a glass terrarium in the studio until spring. One time she rescued a turtle from almost certain death on the high-way and he lived to pose and enrich some book with his grotesque beauty and intricate patterns. It is only by living with a turtle that one can know what a turtle does and why. Another time she brought home a young chipmunk that had been injured by a cat. He was nursed back to health and eventually returned to the woods a wiser chipmunk, we hope! Before leaving he paid for his peanuts and sunflower seeds by posing the best way he knew bow - jumping to her drawing table for a reward and whisking away in the flick of his tail.

Whenever possible my sister likes to have models before her as she draws, but there have been no whales, lions, giraffes or sea serpents in our studio, or rarely any of the other animals found in Animals of the Bible. Photographs and animal anatomies: had to help her construct those she could not find even in zoos. But for leviathan she relied upon her own vivid imagination. This book came after many years of careful study and drawing from nature. I think that it has one of the finest sets of drawings that she has ever done - a worthy recipient of the Caldecott Medal.

Between the making of books she has turned to wood engraving and has already won four prizes for her prints. She enjoys the cutting of the blocks and finds it a satisfaction to have the whole process from the making of the drawing to the pulling of the print from the block under her own hand. As in her books, most of her subjects have been little creatures in their natural environment - a flying squirrel in snow-capped pine branches, a couple of little red efts among rock ferns and grey lichen cups, and a snail with a group of Indian pipes towering above it. One of the most technically excellent and exquisite is that of a fantail goldfish with its delicate, transparent tail floating across the pebbles and weeds of the aquarium. I remember thinking that this print would never be finished, for dozens of proofs were pulled and correction after correction made before she was satisfied to go ahead with the laborious task of making each print of the edition of one hundred and fifty by hand. As a result each print was as perfect as all the others.

Her life's work has been the making of books for children. She has never wanted to draw down to a child, giving him only the crude outlines which are all that he, with his limited experience and skill, is capable of producing - a practice so much the fashion these days. She has always felt that a child with his fresh vision sees more detail than we any longer remember to observe. How often a little boy, looking at one of our flying squirrels, has exclaimed, "What big eyes he has! Look at the tiny little nails on his fingers! His tail is just like a feather, isn't it?" And again, " How soft be looks! Will he mind if I touch him?" The greatest compliment, my sister says, that she ever received was when a child, looking at a drawing of one of these little squirrels, reached out and stroked the pictured fur.

Let Them Live was the outgrowth of her concern for the creatures so hard pressed in a world which men feel belongs only to them. She has an intense desire to present animals in all the fascination of their own animal personalities and ways. I cannot help feeling that thousands of children who never have the opportunity of meeting face to face the creatures who dwell all around them in the woods and fields, are richer in their knowledge of them and their lives because of her books. Perhaps, remembering her pictures, some children will stay their hands and let their fellow creatures live. Perhaps some child may even remember that a turtle's legs are short and his ' steps are slow and will help him to cross the road in safety. That would please her, 1 know, much more than any praise of her drawings. That would make her feel that the countless hours at her drawing board had been worth while.

I heard the fairies in a ring - Down-Adown-Derry; A book of Fairy Poems by Walter De La Mare; published by Constable & Co, 1922

Down-Adown-Derry, A Book of Fairy Poems by Walter De La Mare, Illustrated by Dorothy P. Lathrop

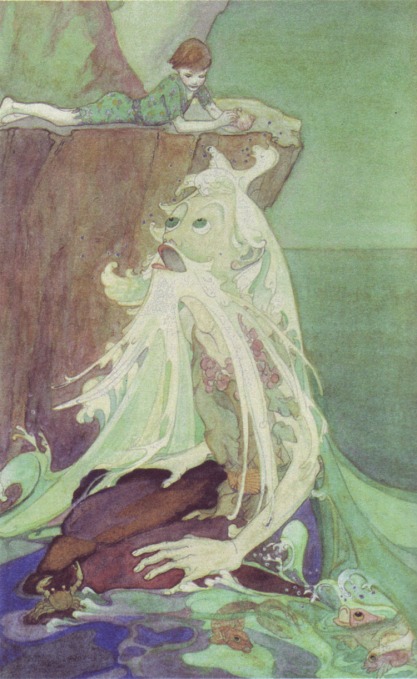

Art by Dorothy Lathrop (1931) from DOWN ADOWN DERRY.”

Art of Narrative: Dorothy Lathrop ~ The Little Mermaid ~ 1939

A statue of the purest white marble - The Little Mermaid, published by The Macmillan Company in 1939

Dorothy Lathrop Sung under the silver umbrella

Dorothy Lathrop, 1918

Let them Live ~ Dorothy Lathrop ~ 1951

Dorothy Lathrop, 1936, The Story of a Tiger

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten