(1874-1944)

The second of seven children, O’Neill was born on June 25, 1874 in Wilkesbarre, Pennsylvania. Her parents, Asenath Cecilia Smith and William Patrick O’Neill, were both creative souls and always encouraged O’Neill in her artistic endeavors, which included writing, acting and drawing. Through her father, a book dealer, she learned to appreciate good literature. When O’Neill was three years old, the family moved to Nebraska. Studying at the Sacred Heart Convent in Omaha, she preferred music, art and drama. In 1890, O’Neill briefly joined a company of touring actors but found the Shakespearean role too challenging. Three years later, she moved to New York to live at the Convent of the Sisters of Saint Regis while the rest of her family moved to the Ozark mountains in Missouri. O’Neill was self-trained as an artist and had no formal art training except for a few classes in while living in New York. Professional Career With nuns accompanying her on her sales calls, O’Neill sold illustrations to many of the prominent periodicals.. Her work appeared in such magazines as Collier’s, Truth, McClure’s and Harper’s. Because the field was dominated by men at this time, she signed her work with her initials “C.R.O.” to conceal the fact that she was a woman. Gray Latham was a young man that O’Neill had met while living in Nebraska. They married in 1896 and lived in New York where she worked as a staff artist for Puck, producing over 700 illustrations over the next few years. She now signed her work as “O’Neill-Latham” and Gray modeled and appeared in many of O’Neill’s illustrations. The marriage was not a happy one though and they divorced in 1901. She quit Puck and returned to the family home in the Ozarks called Bonniebrook where she continued to do work for magazines. Bonniebrook was to become her safe haven in times of turmoil. She married Harry Leon Wilson, the literary editor for Puck, about a year later. He resigned from Puck and they moved to Connecticut to pursue their writing. She illustrated her husband’s novels and her first novel, The Loves of Edwy, was published in 1904. She would eventually write three more novels, The Lady in the White Veil, The Master Mistress, Garda and The Goblin Woman and a book of poetry. O’Neill, who had a vivacious and outgoing personality, despised her husband’s moodiness and silence and she divorced him in 1908. It has also been suggested that it was her propensity for baby talk that may have broken up her marriage. Disappointed and melancholy, she returned to Bonniebrook once more. It was here that the plump little elf-like creatures called Kewpies came to her, literally. She claims that they appeared to her in a dream and when she awoke, they were all over her room. In actuality, she had been drawing little cupids as headpieces and tailpieces for her magazine work. In 1909, Edward Bok suggested to her that she do a series of drawings featuring the little creatures as the main character. They were inspired by her baby brother and Cupid, the god of love, “but there is a difference,” she said. “Cupid gets himself into trouble. The Kewpies get themselves out, always searching out ways to make the world better and funnier.” They made their first public appearance in Woman’s Home Companion in December of 1909. They were immediately popular and quickly became a large merchandising industry. O’Neill was commisioned for her Kewpie designs for magazine stories, paperdolls, and advertisements appearing in Good Housekeeping and Ladies’ Home Journal as well as other periodicals, and as a comic strip for The New York Journal in the 1930’s. Popular at this time were the ‘Kewpie Kutouts’, the first of its kind double-sided paper doll. The first Kewpie children’s book appeared in 1910, followed by two more in 1912 and the last one in 1928. Geo. Borgfeldt & Co. of New York was interested in producing a line of dolls and figurines in 1912. They were eventually granted control of all production rights to Kewpie dolls and figurines. A young artist, Joseph Kallus of Brooklyn, studying at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn was chosen to sculpt a line of Kewpie figurines, an event that was to change the course of his intended career. The dolls were economically produced in Germany by the J.D. Kestner Co.out of porcelain, briefly stopping production during World War I. O’Neill lived well off of her commissions and royalties and became the highest paid woman illustrator of her time. Estimates at the time of her death place her earnings at around $1.4 million . Her sister Callista became O’Neill’s business manager and must be credited for her market savvy. O’Neill began to travel and had many well-known friends in the art world. Two of her later creations were Scootles and Ho-Ho. Scootles was similar to Kewpie in shape but depicted a real child rather than an elf. Ho-Ho was a laughing Buddha that was not well received by the Buddhist community. She also drew what she called her “Sweet Monsters”, drawings of sensuous mythical creatures. She considered these to be her serious work. The Amsterdam Theater on 42nd Street in New York was the site of a Kewpie musical production in 1919. A song based on the artist, ‘Rose of Washington Square’ (referring to the address of her New York apaprtment) was first performed here. Negotiations had started with a movie studio to produce a movie featuring Kewpie but the project fell through. O’Neill was also known for her portrayal of blacks in her cartoons. While they were somewhat stereotypical, they were treated with dignity. Years of overspending and financial setbacks sent O’Neill retreating back to Bonniebrook where she wrote her memoires. After suffering several strokes, O’Neill died on April 6, 1944. She was buried next to her parents at Bonniebrook. Before she died, she had donated some of her work to The School of the Ozarks, a college located at Point Lookout, Missouri where they have established a museum to house their extensive collection of Rose O’Neill memorabilia. Influences O’Neill enjoyed reading classical literature as a child, including the Greek myths, from which Kewpie was obviously inspired by. In her later years, she chose a mode of dress similar to the flowing gowns of classical Greece. While in Paris, she studied under the sculptor Rodin and the writer Kahil Gibran. She was also known to enjoy the work of the Symbolist movement, Gustave Doré and William Blake. Raison D’Être Her personal philosophy was, “Do good deeds in a funny way. The world needs to laugh or at least smile more than it does.” Through her artwork, she spread this concept to the world, Kewpie being her most trustworthy ambassador.

| |

| Puck, December, 1903. | |

| Harper's Bazar, 1906. | |

| The Kewpies Their Book, Frederick A. Stokes, 1911. | |

| The Kewpies Their Book, Frederick A. Stokes, 1911. | |

| The Kewpies Their Book, Frederick A. Stokes, 1911. | |

| The Kewpie Kutouts, Frederick A. Stokes, 1914. | |

| The Kewpie Kutouts, Frederick A. Stokes, 1914. | |

| Jell-O Advertisement from Pictorial Review, March, 1919. | |

| "Kewpieville", Ladies Home Journal, April, 1925. | |

| Kewpies and the Runaway Babies, 1928. |

“She sings with a great deal of expression, doesn't she?”

“Yes, I wonder she has any face left.”

Harper's New Monthly Magazine, 1898.

When the Kewpies were introduced to a new magazine, they arrived with much fanfare. This introduction, written by Rose O'Neill, is from June, 1914.

The Kewpies Arrive (We Told You They Were Coming---Here They Are!

Oh, children dear, come here, come hear and see! Come look, and leave your bread-and-buttering: For something queer is flying near---and see What tiny wings all flipping, fluttering! The sun on every topknot, glittering! Like flocks of little birds all flittering! Their pretty little words all twittering--- Why, I declare they're Kewpies!

An early Kewpie Kutout page, Woman's Home Companion, November 1914. Rose O'Neill was the first artist to produce two-sided paper dolls and clothing.

“In the Reign of Alfred Don't,” American Magazine, c.1908.

THE DARKER SIDE OF ROSE O ' NEILLE

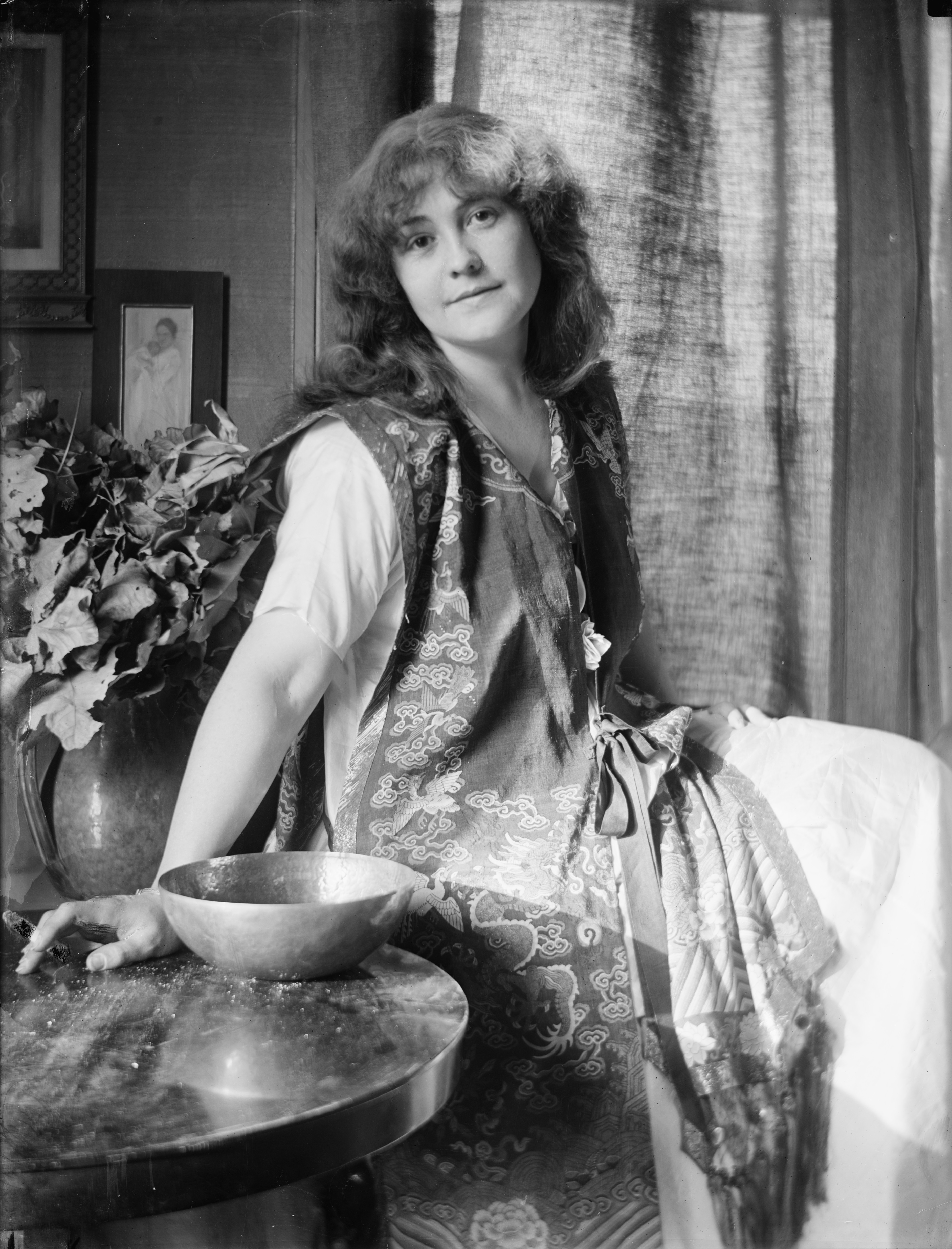

Rose preferred to wear flowing robe-dresses which she called an aura or a mantle. Ozark natives on the other hand called them “flyin’-squirrel dresses.” Her garments might not have looked like anything other women were wearing at the time, but they allowed Rose to have the movement needed to create works of art. Other women of the time period were wearing corsets in which they could barely breathe in let alone create art! In 1915 to The New York Press Rose said: “The first step is to free women from the yoke of modern fashions and modern dress. How can they hope to compete with men when they are boxed up tight in the clothes that are worn today?”

The Bonniebrook Historical Society has been working hard to get Rose Cecil O’Neill nominated to the Hall of Famous Missourians (located in Jefferson City, Missouri in the 3rd Floor Rotunda of the Missouri State Capitol). It is surprising that she has yet to be nominated because of the fact that several of Rose’s acquaintances are already honored there. Thomas Hart Benton, John Neihardt, Laura Ingalls Wilder, Walt Disney and Mark Twain are just a few of the individuals that she knew who already have a bronze bust in their image located there. Rose’s Kewpies were on the same level of popularity as that of Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse, and reportedly Thomas Hart Benton said that Rose was the world’s greatest illustrator. There are over 40 bronze busts depicting prominent Missourians who are honored for their achievements and contributions to the state, and if you think that Rose should be honored as well, please leave a comment on this post explaining why you support Rose to be considered for this prestigious award. We would greatly appreciate your support as the Hall is visited by thousands of school children and vacationing families every year, and if Rose was featured there it would assist in our educating about the many accomplishments of the genius of the arts, Rose Cecil O’Neill.

Illustration from Good Housekeeping Magazine

Illustration from Harper's Magazine

Illustration from Puck Magazine

In 1995, the Missouri House of Representatives honored Rose O'Neill with the prestigious Missourian Award. It is now time for her to be honored in the Hall of Famous Missourians.

Almost thirty years after Rose O’Neill dreamed up the idea for the Kewpie, she came up with one last idea before she retired: the Ho-Ho. The Ho-Hos look like little laughing Buddha figures. They have a very unique laughing expression in which Rose O’Neill says that she had the idea for for years. Rose said, “year by year, as the world grew less and less funny, the laugh got clearer in my mind. It is the sort of laugh that makes a laugh in the beholder, as kindness makes the warmth of returning kindness. Ho-Ho is a sort of little clown-Buddha, all his stored-up wisdom finding its last word in the supreme wisdom of laughter. This kind of laughter is man’s final defense against despair.” It is sad that the Ho-Ho was Rose’s last creation because it was not very successful.

This photo of Rose holding a Ho-Ho was taken shortly before she passed away.

Rose sitting in the woods with her last creations.

Box for the Kewpie Dolls

Rose O'Neill at Bonniebrook circa 1930

Rose O'Neill led a fascinating life. She did everything on her own terms. Married and divorced twice by 1909, O'Neill chose to be childless. She supported her large family and paid to educate her brothers and sisters. O'Neill is best remembered for inventing the Kewpie character and the merchandising boom that followed.

The income from her illustrations and Kewpie merchandise allowed her the freedom to study art in Paris and create what she named her "Sweet Monsters". These were shown in Paris in 1921 and again in New York in 1922.

This is how she described her creative process:

O'Neill studying art in Paris circa 1906

Consciousness

The Red Fauness

Capri 1933

Paris Exhibition Catalog 1921

New York Exhibition Catalog 1922

The income from her illustrations and Kewpie merchandise allowed her the freedom to study art in Paris and create what she named her "Sweet Monsters". These were shown in Paris in 1921 and again in New York in 1922.

This is how she described her creative process:

"When the guests were gone I used to draw at night. Now that I had plenty of money I did not illustrate as much but let my hand have free play. I would pull up the big rocking chair under the light and let myself go. I am ashamed to be seen when I suffer or when I toil. In the latter case my consciousness has gone away. I leave my cadaver behind and I am embarrassed like a suicide. Often I would have no plan before beginning. The plan seemed hidden in the hand itself. Then satyr-like heads and half-beastly shapes would appear on the paper and the Idea would loom. Marvelous nights! With the sound of passers in the Square growing few -- perhaps a moon crossing the sky beyond my large highWINDOWSand the rustling images of ancestral things surging through my head and projecting themselves upon my paper all wrapped in mesh of endless convolutions. Late in the night I would get out of the "Drunken Sailor" (her rocking chair) and, half drunk myself with visions, lay my drawing or drawings (sometimes there would be several) in the portfolio and stagger off to bed. Another monster had been born.

I seemed to be entranced by the idea of the rise of man from animal origins and was always drawing low slant-browed beings that pointed the road behind us. These beings charmed me. They seemed to have the freshness of leaves, the rugged well-being of the rocks themselves. I made them with great necks curved like a stallion's. We called these drawings "the monsters". Meemie (mother) complained of them. She had a literal eye. I made these drawings in an intricate network of lines with a small brush and India ink. Meemie said she did not like to see the figures "all tied up in a web." I said, "Why make it with a few lines when you can make it with many?" The web of lines took time. And that was the fun of it. Not to conclude -- to go on deliriously sculpturing the form, prolonging the delight. While I drew them, I had ecstatic images of the up-surge of life from the "ancestral slime". This progression seemed to me the epic of epics. People used to wonder how the hand that made the Kewpies could bring forth those monstrous shapes µµwith their mysterious whisperings of natural forces and eons of developing time

O'Neill studying art in Paris circa 1906

Consciousness

The Red Fauness

Capri 1933

Paris Exhibition Catalog 1921

New York Exhibition Catalog 1922

The Rose O’Neill Museum is located in the Ozarks Hills of Taney County near Branson, Missouri at 485 Rose O’Neill Road in the town of Walnut Shade. The museum is housed inside the Bonniebrook House, a recreation of the O’Neill family’s 14 room estate.

The museum contains hundreds of Kewpie ephemera (from dolls to door knockers) that showcase O’Neill’s successful life as an artist/sculptor/author/activist.

Born in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania on June 25, 1874, Rose Cecil O’Neill was an American artist who created a magical creature called a Kewpie who was modeled after Cupid, the Roman God of Love.

“Do good deeds in a funny way. The world needs to laugh or at least smile more than it does.” — Rose O’Neill

Rose O’Neill is buried on the grounds of Bonniebrook estate, along with other family members, including her mother, father and her sister, Callista.

In her heyday, Rose O’Neill was called “The Queen of Bohemian Society.” While living in Greenwich Village, Rose became the inspiration for the popular song “Rose of Washington Square.”

They call me Rose of Washington Square.

I’m withering there, in basement air I’m fading.

Pose in plain or fancy clothes?

They say my roman nose

It seems to please artistic people.

Beaus, I’ve plenty of those.

With second-hand clothes, and nice long hair!

I’ve got those Broadway vampires lashed to the mast.

I’ve got no future, but oh! What a past.

I’m Rose of Washington Square.

Rose O'Neill and Thomas Hart Benton

Bonniebrook, Home of Rose O'Neill.

Rose at Bonniebrook with a housekeeper

Rose with sister Callista en brother Clink

Rose at home

Rose as a baby ca 1874

Rose O’Neill, after a three-year stint as a child actress, then in 1893 she entered and subsequently left the convent. She married Grey Latham in 1896.

Rose and her sister Callista with a kewpie doll

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten